# Andrew Crosse: The 19th Century Scientist Who Sparked Controversy

Written on

Chapter 1: Early Life and Education

Andrew Crosse was born in June 1784 into a wealthy family in Somerset. A prodigy in languages, he mastered Ancient Greek by the age of eight. His passion for science blossomed at Dr. Seyer’s School in Bristol, where he developed a keen interest in electricity by twelve. Had it not been for his family's wealth, Crosse might have faced expulsion for his mischievous experiments, which included wiring classroom doorknobs to an electric accumulator to surprise teachers with shocks.

Following his mother's passing in 1805, he inherited the family fortune and established a well-equipped laboratory at home. This marked the beginning of his lifelong obsession with electrical experiments.

Crosse utilized an extensive network of copper wires, stretching over a mile, emanating from his lab like a vast web. This installation allowed him to harness lightning's power, giving Fyne Court, his remote country mansion, a reputation for the supernatural. Local residents, steeped in superstition, would gather to watch lightning dance along the wires during storms, convinced that Crosse was dabbling in dark arts, when, in fact, he was merely experimenting with the immense voltages produced by nature.

Chapter 2: The Insect Experiment

Crosse's scientific curiosity extended beyond mere observation; he meticulously documented the crystals formed from electrical currents passing through mineral solutions. In an entry from 1837, he recounted a bizarre incident that remains unexplained:

"In my quest to synthesize artificial minerals through prolonged electrical action on suitable fluid solutions, I devised various setups. Among them, I built a wooden frame supporting a Wedgewood funnel, with a quart basin placed atop a mahogany disc. When the basin was filled with liquid, a flannel strip soaked in the same fluid hung over the basin's edge, allowing it to siphon out in droplets. These droplets then fell into a smaller glass funnel containing porous red oxide from Vesuvius, which was kept electrified."

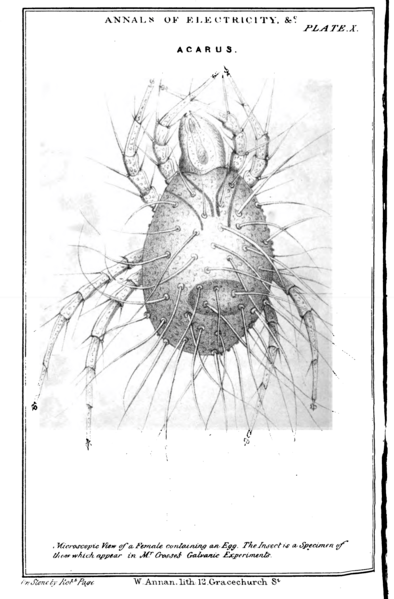

On the fourteenth day of this experiment, he observed small, white projections on the electrified stone. By the eighteenth day, these projections had expanded and sprouted several filaments. By the twenty-sixth day, they had transformed into a complete insect, and by the twenty-eighth day, these creatures were moving their legs.

Crosse was utterly astonished by the unexpected outcome and sought a rational explanation for the peculiar insects. He immediately replicated the experiment, documenting:

"After extensive action and the formation of certain crystalline substances, I noted similar projections at the fluid's edge in almost all cylinders, except for two containing specific compounds. Eventually, these white formations developed into insects."

Despite his findings, Crosse remained skeptical. He recounted that he had neglected to provide a resting space for the acari, which are typically destroyed if they fall back into their originating fluid. He noted the oddity of a single acarus appearing in a highly caustic solution and under an atmosphere of oxygen-hydrogen gas.

Crosse's peculiar discovery was presented in detail to the London Electrical Society. Although met with skepticism, the Society commissioned W. H. Weeks, a reputable researcher, to replicate Crosse's experiment. Weeks conducted his work with meticulous care, disinfecting everything and isolating himself during the process.

News of Crosse's experiment spread quickly after it was reported in a West of England newspaper, garnering attention throughout Britain and Europe. Weeks ultimately claimed to have replicated the unusual insects.

Chapter 3: Controversy and Legacy

The usually reclusive Crosse suddenly found himself at the center of a media frenzy. While many in the scientific community hailed him as a genius, the ecclesiastical establishment and the general public were horrified by what they perceived as "blasphemy." They regarded him as a meddling figure challenging divine authority.

Upon returning to Fyne Court, Crosse faced hostility from locals who vandalized his property, killed his livestock, and set fire to his crops. The Reverend Philip Smith, who incited much of this unrest, even conducted an exorcism on Crosse’s estate.

On July 6, 1855, the controversial scientist passed away after suffering a paralytic seizure. His final words were, “The utmost extent of human knowledge is but comparative ignorance.”

Even today, scientists remain baffled by the acari that Crosse reportedly created, and few are willing to replicate his extraordinary 19th-century experiment. One can't help but wonder if Mary Shelley, intrigued by Crosse's work, drew inspiration for elements of her 1816 novel "Frankenstein," particularly the concept of using lightning to generate life.

For more intriguing historical insights, check out my Lists:

British History

Science

For updates and additional content, follow my Twitter feed @welfordwrites.

Join Medium to explore more of my writings and those of other members. Please note that a portion of your membership fee will support my work.