# Can Beige Fat Shield Your Brain from Dementia? Insights from Research

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Fat Types

When we think about body fat, the extra padding around the waist typically comes to mind; this is primarily white fat.

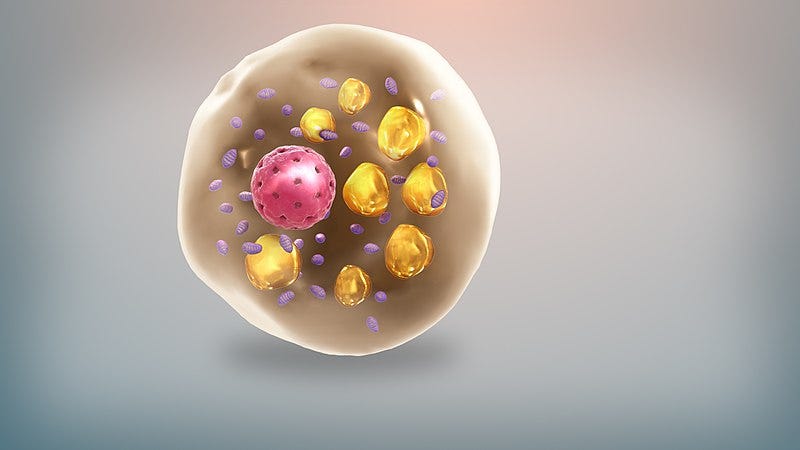

White adipose tissue serves as the body's energy reservoir, consisting of large fat droplets. It accumulates in two main areas: around internal organs (intra-abdominal) and just beneath the skin (subcutaneous). Most adults have sufficient amounts of white fat.

In contrast, brown fat contains numerous smaller fat droplets and is rich in energy-producing mitochondria. This type of fat is thermogenic, meaning it generates heat. Infants and hibernating animals possess significant amounts of brown fat, but its presence diminishes with age. It usually accumulates around the shoulder blades, neck, spine, and kidneys.

A newer category is beige fat, characterized by its brownish hue and dispersed among white fat cells. While it resembles brown fat, it is not identical, having varying sizes of lipid droplets and slightly fewer mitochondria.

The remarkable aspect of beige fat is its ability to form from white fat; this conversion can be stimulated through methods like cold exposure and physical activity. Although it’s a challenge to significantly replace white fat with beige, it remains a noteworthy possibility. Beige fat is metabolically active, aiding in calorie burning, which is why researchers are investigating its potential in addressing obesity.

Chapter 2: Beige Fat and Brain Health

Recent research involving mice suggests that beige fat may offer protection against brain inflammation and cognitive decline, potentially contributing to dementia prevention.

The study began by disabling the genes responsible for beige fat development in a group of mice, resulting in their subcutaneous fat turning as white as a polar bear in the snow. When these mice were placed on a high-fat, calorie-rich diet, they gained weight—an expected outcome also seen in control mice.

However, the white-fat-only mice exhibited cognitive impairments. It was discovered that the microglia in these mice began to produce inflammatory molecules. While the control mice also showed similar reactions, they activated anti-inflammatory molecules that the white-fat mice lacked, leaving them unable to combat the resulting inflammation.

In an intriguing twist, researchers transplanted subcutaneous beige fat from healthy young mice into the white-fat, obese mice that were showing signs of cognitive decline. Remarkably, this led to improvements in memory and restored synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus, a crucial area for learning and memory.

The positive effects were linked to the anti-inflammatory molecule IL-4, which the beige fat stimulated microglia and T cells in the brain to produce, thereby reducing inflammation.

The researchers concluded that "these findings indicate that beige adipocytes oppose obesity-induced cognitive impairment, with a potential role for IL4 in the relationship between beige fat and brain function."

While the results are promising, it's essential to note that these experiments were conducted on mice, and further investigation is necessary to confirm the findings in humans. Factors such as gender differences in fat cell response and the impact on non-obese mice remain to be explored.

In the meantime, embracing activities that promote beige fat development, like cold showers, might be a beneficial step.