The Enigmatic Builders of Göbekli Tepe: Unraveling the Mystery

Written on

Göbekli Tepe: An Archaeological Wonder

Göbekli Tepe has emerged as one of the most significant archaeological finds in recent years. Situated in Turkey’s ?anl?urfa Province, it has sparked intense debate about the roots of organized religion and agriculture.

Constructed between 9600 and 8700 BC, the megaliths at Göbekli Tepe have intrigued alternative historians who suggest they were created by survivors of a lost Ice Age civilization. Some even theorize that it was the Garden of Eden or the work of the Sumerian deities known as the Anunnaki. However, such claims lack substantial evidence.

My introduction to Göbekli Tepe occurred in 2020 through a piece by Oliver Dietrich, who has been actively involved in excavations since 2005. His insights and unique images motivated me to explore this site further.

As one of the leading archaeologists at Göbekli Tepe, Dietrich's findings have evolved significantly over the past few years. Previously held notions, such as the site's original classification as a temple, are now being reconsidered. With only a fraction of the area excavated, much of our current understanding may soon require revision, showcasing the ever-changing nature of archaeology.

This article will delve into the mysterious individuals who constructed Göbekli Tepe, examining their identity and whether a social hierarchy existed that facilitated such an ambitious undertaking. Before investigating the builders of this ancient monument, let’s take a closer look at the site itself.

Göbekli Tepe: A Comprehensive Overview

Göbekli Tepe was initially uncovered during a University of Chicago archaeological survey in 1963 but was largely overlooked until Klaus Schmidt re-identified the site in 1995 and began excavations.

Located in the Ta? Tepeler (Stone Hills) at the base of the Taurus Mountains, Göbekli Tepe overlooks the Harran Plain and is part of a region rich in archaeological sites from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) era.

The PPN period is characterized by a lack of pottery and marks the early stages of crop and animal domestication. It is divided into two phases: PPNA (approximately 10,000 to 8700 BC) and PPNB (8800 to 6500 BC). Göbekli Tepe belongs to the PPNA era, where a blend of sedentary and hunting-gathering lifestyles was observed.

The site features four circular enclosures—designated A, B, C, and D—ranging from 10 to 30 meters in diameter. Geophysical surveys suggest there are 16 additional similar enclosures, alongside smaller rectangular structures.

Each circular enclosure houses two massive T-shaped pillars, approximately 5.5 meters tall, surrounded by numerous smaller T-pillars. Research indicates there could be around 200 such pillars, depicting various human and animal figures, predominantly male.

Among these, foxes, boars, cranes, snakes, leopards, and vultures are frequently represented. Current studies are focused on interpreting the symbolism behind these T-pillars.

Initially, Schmidt posited that Göbekli Tepe functioned as a temple where hunter-gatherers congregated for rituals. He speculated that its creators were not sedentary due to the scarcity of water sources and the lack of residential structures. Instead, they were believed to gather for religious ceremonies and communal feasts.

Following Schmidt's passing in 2014, new discoveries have surfaced that challenge his original assessments. The idea that hunter-gatherers built Göbekli Tepe is now under scrutiny.

Hunter-Gatherers or Early Farmers?

Traditionally, it has been thought that humans transitioned from nomadic hunter-gatherer societies to settled agricultural communities around 11,000 years ago, following a climate shift that favored farming. However, archaeological evidence does not fully support this narrative.

In a previous discussion, I highlighted some of the earliest permanent settlements, such as Dolní V?stonice in the Czech Republic, which date back 26,000 years, during the peak of the Ice Age. The shift to sedentism was gradual and multifaceted.

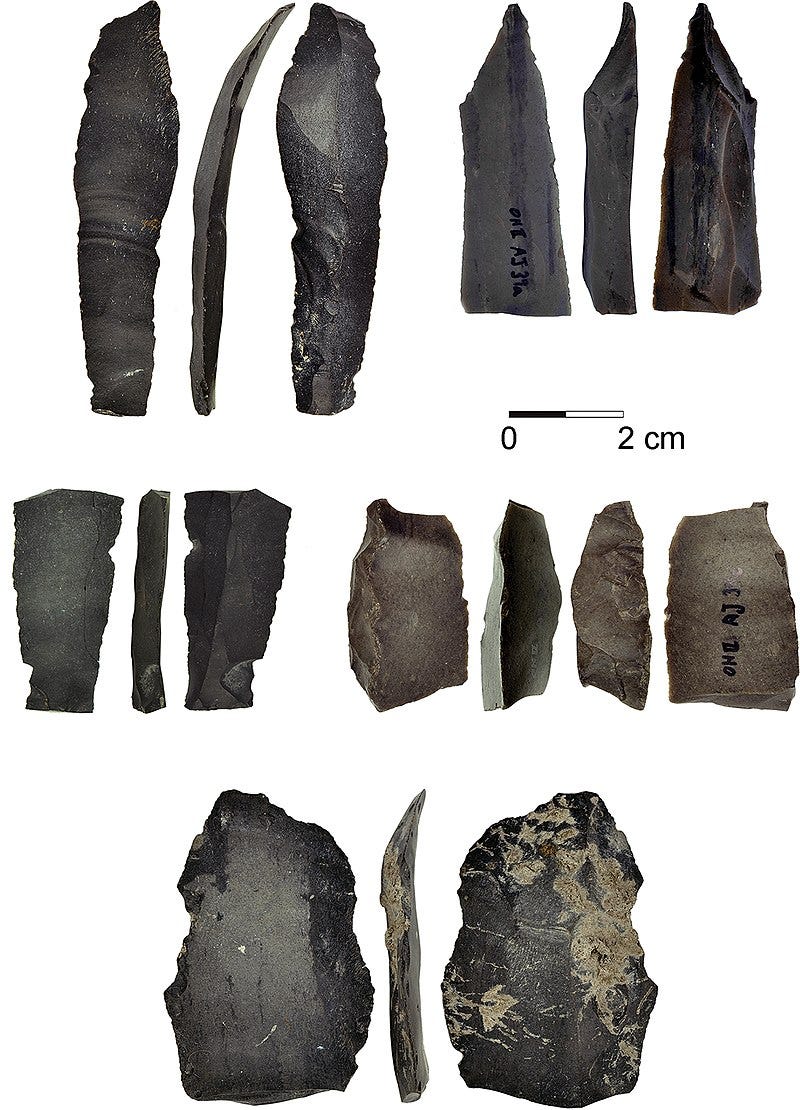

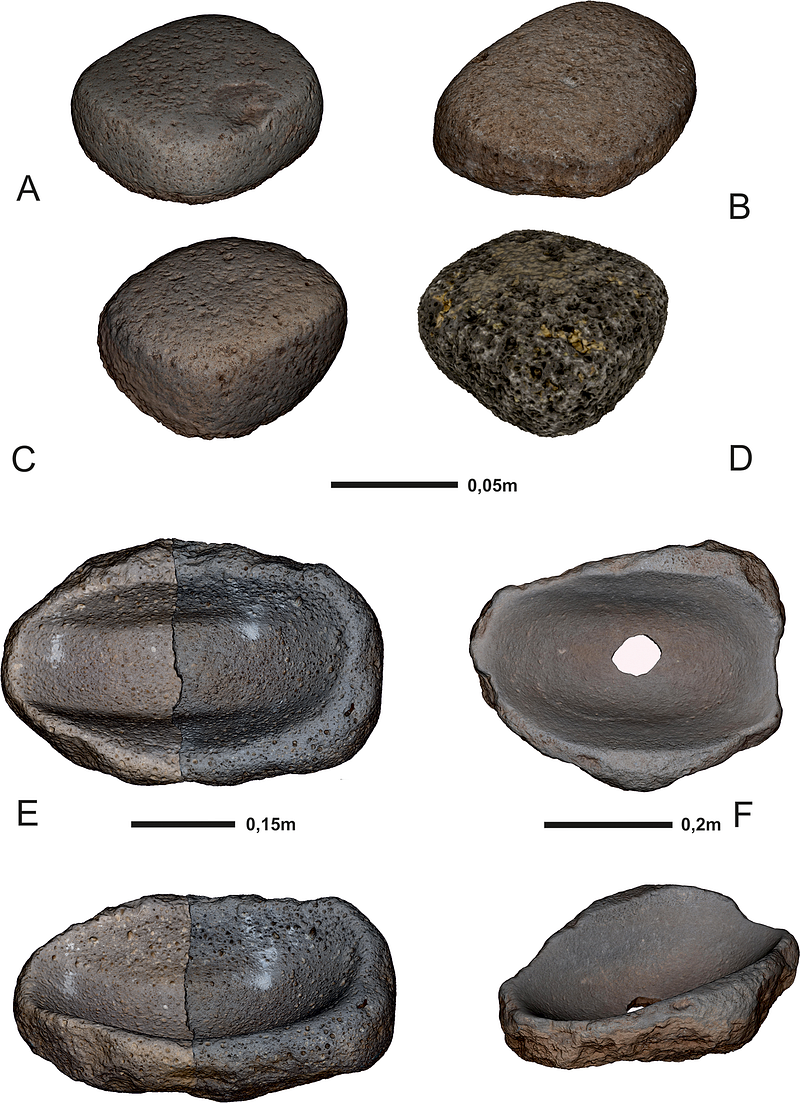

Long before adopting agriculture, humans were already processing and cultivating wild grains. Evidence of grain processing in the Near East dates back to around 23,000 years ago at the Paleolithic site of Ohalo II in northern Israel.

The Natufian culture (15,000 to 11,500 years ago) in present-day Israel exhibited semi-sedentary traits, with communities engaged in grain processing, hunting, and beer brewing.

At Göbekli Tepe, a semi-sedentary culture similar to the Natufians can be observed, as the inhabitants were transitioning toward settled life while still relying heavily on hunting.

During summer months, large groups involved in the construction of the megaliths would come together for hunting expeditions and communal meals.

Dietrich noted:

> "There is evidence for extensive plant food processing and archaeozoological data hint at large-scale hunting of gazelle between midsummer and autumn. As no large storage facilities have been identified, we argue for a production of food for immediate use and interpret these seasonal peaks in activity at the site as evidence for the organization of large work feasts."

Schmidt asserted that hunter-gatherers constructed Göbekli Tepe because the mountaintop was thought to lack adequate water supply. However, a large cistern capable of holding over 15,000 cubic meters of rainwater was found, challenging this assumption.

Recent geophysical surveys reveal that the water table may have been higher during the PPNA period, possibly supporting nearby springs. The primary cistern was connected to multiple underground cisterns, suggesting a greater potential for water storage than previously believed.

Archaeologists argue that the notion of a distinct place of worship separate from residential areas is a modern, secular concept. The inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe may not have drawn such distinctions; they could have worshipped and lived in the same spaces.

Rectangular structures adjacent to circular enclosures hint at a semi-sedentary lifestyle, suggesting that people may have resided at Göbekli Tepe for much of the year.

While we have moved beyond Schmidt's hunter-gatherer theory, it remains evident that Göbekli Tepe predates fully developed agriculture and animal domestication. Although the inhabitants had begun experimenting with wild grains and herding, leadership was likely necessary to coordinate the megalithic construction.

This raises the question: did the society at Göbekli Tepe have an elite class?

The Influential Figures of Göbekli Tepe

During the PPNA period, there were no centralized authorities like pharaohs or priest-kings to oversee major projects. In cultures predating state formation, what motivated people to undertake such monumental tasks?

Earlier this year, I participated in a webinar led by Lee Clare, one of the site’s leading archaeologists. Clare emphasized the importance of charisma in motivating prehistoric societies to engage in ambitious endeavors.

Quoting archaeologist Jacques Cauvin, Clare suggests that certain "inspired individuals" in prehistoric communities wielded significant influence during specific periods. For instance, several Paleo-Indian tribes had war leaders who emerged only during conflicts. At Göbekli Tepe, select individuals may have directed efforts during construction and ritual feasts, effectively forming a societal elite.

Clare categorizes these "inspired individuals" into three groups: - The ritually adept - The storyteller - The hunter

It is likely that some individuals belonged to more than one category.

Archaeologists propose that shamans, or "the ritually adept," held considerable sway at Göbekli Tepe. During the Paleolithic era, shamans were pivotal, transitioning from animistic roles to formal priesthoods as societies settled.

Schmidt remarked:

> "It seems probable that the shamans of Göbekli Tepe had been 'at the edge.' The edge to cross the border from the animistic shaman to the established priest. Some motives of the reliefs and sculptures are still the old ones, but they seem mixed with the dawn of representations of a new world, a world of temples with powerful rulers, a world of classified society."

What evidence exists to substantiate the influence of shamans at Göbekli Tepe?

One argument is the prevalent depictions of death at the site, as shamans were crucial in interpreting death and the afterlife within prehistoric cultures. Archaeologists suspect a death cult existed at Göbekli Tepe and its surrounding PPN sites.

Some figures at Göbekli Tepe exhibit visible ribs, suggesting a ritualistic practice of excarnation, where flesh is removed before burial. This method continues in some cultures today. A panel featuring vultures with a headless human could further support this theory.

Evidence of human skull worship and the early development of a skull cult has also been found at Göbekli Tepe, a practice that gained prominence throughout the Fertile Crescent during the PPNB period. In cultures where shamans held significant power, skulls were revered and preserved.

In addition to shamans, storytellers played an integral role at Göbekli Tepe. Clare suggests that the imagery on the T-pillars conveyed oral traditions passed down through generations, vital for preserving knowledge and cultural practices.

Clare theorizes that the stories represented on each pillar were unique to specific clans, independent from those on other pillars.

If this hypothesis holds, what kinds of narratives were being depicted?

Archaeologists believe that significant depictions of death reflect legends associated with a death cult passed down through the ages. Notably, the image of a vulture carrying a headless man may represent a Neolithic myth linked to mortality.

Storytellers may have gained elevated social status by leveraging their knowledge and narrative skills, thus earning respect and becoming preferred social partners. Clare posits that prestige and influence could have propelled storytellers to elite status, although archaeological evidence remains lacking.

The animal representations at Göbekli Tepe predominantly feature predators or aggressive species like foxes, wild boars, scorpions, leopards, and aurochs, often depicted in menacing poses. While non-threatening animals like cranes and ducks are present, they are less common.

This leads us to consider the role of hunters in this societal structure.

Could the imagery of fierce creatures suggest that hunting was a revered activity, elevating exceptional hunters in societal esteem?

A recently uncovered relief at the Sayburç site near Göbekli Tepe illustrates a human figure alongside an aurochs, further flanked by two leopards. The depiction of the individual teasing the aurochs, while holding what was initially thought to be a snake, is now interpreted as a severed part of the aurochs, perhaps indicating a "coming of age" ceremony or initiation rite reflecting the hunter's elevated status in society.

Our understanding of Göbekli Tepe has expanded significantly in recent years. We now have a clearer picture of the society that erected these remarkable megaliths. They were transitioning from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle toward a more settled existence, on the brink of domesticating plants and animals.

Archaeologists suggest that shamans, storytellers, and hunters—each charismatic members of the community—formed the social elite and guided the monumental projects during this pre-state era.

Despite the advances in our knowledge, much remains to be uncovered. Many interpretations of the site's narratives are subjective. A recent post by Oliver Dietrich encapsulates our ongoing efforts to decode the narrative scenes at Göbekli Tepe:

> "If you stand in front of an image showing the Last Supper lacking any information on the cultural background or ignoring the information others reconstructed, you’ll see a group of people eating. And you can interpret anything into it. That’s happening frequently to Göbekli Tepe." — Oliver Dietrich via X

What are your thoughts on the social classes and narrative scenes at Göbekli Tepe? What messages did the ancients aim to convey?

Feel free to share your insights in the comments. If you found this piece intriguing, explore the story of another ancient city in Anatolia, which shares several characteristics with Göbekli Tepe.

Heaven and Hell Met in This 9000-Year-Old Settlement

The rise and fall of Çatalhöyük