The Hidden Truth Behind Our Struggle with Fake News

Written on

Chapter 1 Understanding Our Cognitive Shortcomings

In today's society, our capacity to differentiate truth from falsehood, particularly in political contexts, seems to be declining. Cognitive science suggests that the prevalent idea of partisan bias as the primary culprit might not tell the whole story.

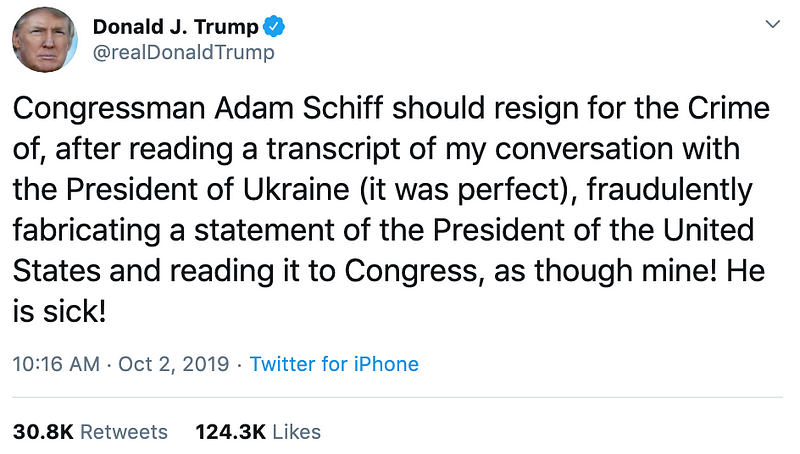

For instance, consider President Donald Trump's tweet accusing Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) of fabricating statements and presenting them to Congress. This tweet referenced Schiff's interpretation of a phone call Trump had with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

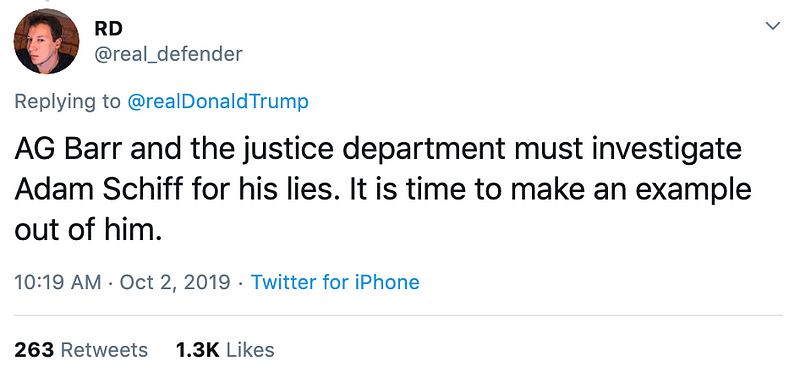

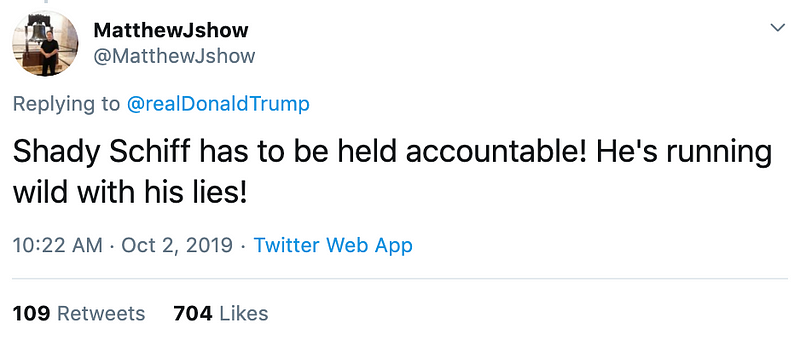

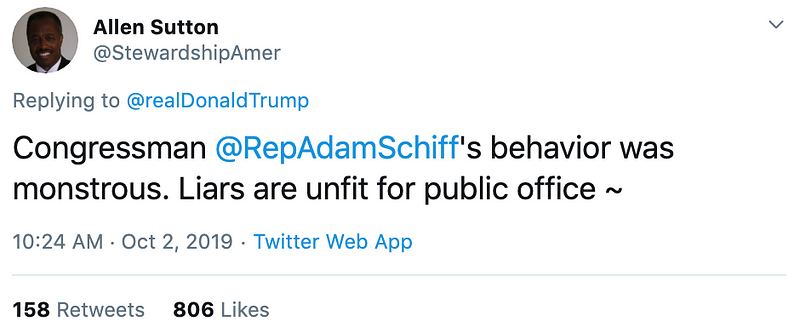

Trump's supporters quickly rallied on social media, arguing that it was Schiff, rather than Trump, who sought damaging information from Ukraine. Some even questioned why Schiff wasn't under investigation, despite a lack of evidence against him.

Numerous examples emerged from influential Twitter users with substantial followings, all responding to Trump's tweet. The division over basic facts only intensified from there. For instance, shortly after the tweet, only 40% of surveyed Republicans believed Trump mentioned Joe Biden during the call, even though he had confirmed this.

Trump further asserted—without evidence—that Schiff had a hand in drafting the whistleblower complaint. Even weeks later, Trump continues to attribute the narrative against him to "fake news."

But why does reality seem so malleable depending on the source of information? Why does it appear that we can no longer agree on a shared factual foundation?

Many attribute this phenomenon to partisanship, suggesting our beliefs shape our interpretation of facts. While there is some validity to this—known as motivated reasoning—this explanation may overlook a critical aspect.

Chapter 2 The Role of Cognitive Laziness

Recent studies propose that our struggles with fake news may not be primarily due to partisanship, but rather our willingness and ability to engage in critical thinking.

Research published in the journal Cognition highlights cognitive laziness as a significant factor in our acceptance of false information. The study, conducted by Gordon Pennycook and David G. Rand, involved 800 participants who evaluated a mix of factual and false headlines. Participants were also assessed on their cognitive reflection abilities.

The findings were surprising. Partisan alignment played a minimal role in distinguishing between true and false news; what mattered more was the individual's analytical skills.

In essence, individuals with strong critical thinking abilities were more likely to reject fake news, irrespective of their political views. This implies that the acceptance of fake news is less about partisan beliefs and more about a lack of cognitive engagement.

The video titled "It's Not Just Fake News. It's Way Worse..." delves deeper into these issues, illustrating how cognitive laziness contributes to the spread of misinformation.

Cognitive Reflection Tests (CRT) were part of this study to gauge reasoning potential. Those with high CRT scores exhibited greater mental acuity and were less inclined to be "cognitive misers"—individuals who prefer quick, uncomplicated answers over thorough analysis.

While mental shortcuts can be beneficial, particularly in everyday decision-making, those who readily accept fake news often operate on cognitive autopilot. They do not engage in motivated reasoning; rather, they fail to reflect at all.

Cognitive misers are not necessarily uninformed or unintelligent; they simply opt for superficial thinking, especially regarding complex issues such as politics.

Though we should exercise caution in generalizing beyond Pennycook and Rand's findings, if their research reflects the reality of our susceptibility to fake news, it also offers valuable insights into addressing this issue.

Chapter 3 Solutions to Combat Cognitive Laziness

The first explanation blames motivated reasoning, suggesting that our brains are actively trying to justify our beliefs based on partisan perspectives. However, the cognitive laziness model indicates that we often absorb information with minimal attention, akin to how we might ignore background noise.

The reasons behind cognitive miserliness remain uncertain. It could stem from time constraints, distractions, feeling overwhelmed by information, or simply a lack of motivation. Sometimes, we just choose to conserve our mental energy.

As we analyze ways to counter disinformation in our current age, we may need to acknowledge that the effectiveness of fake news is rooted in our cognitive complacency. As highlighted by Maggie Selner, if we want to diminish the influence of fake news, it is incumbent upon us to engage more deeply in our thinking.