Olive Oil and Brain Health: A Critical Examination

Written on

Chapter 1: Introduction to Olive Oil and Dementia Risk

As many of you may know, I’m always on the lookout for lifestyle adjustments that are both enjoyable and beneficial to health. However, finding such changes, especially regarding diet, can be quite challenging. My children often express their discontent, claiming that when I mention healthy food, I really mean unappetizing dishes. While French fries are undeniably delicious, they certainly can’t be a daily staple.

Upon encountering an article that suggested olive oil may lower the risk of dementia, my curiosity was piqued. I have a fondness for olive oil, using it frequently in my cooking. Yet, as is typical in nutritional epidemiology, we must approach these findings with caution. There are numerous reasons to question the validity of this study, though one significant point lends some credence.

The research I’m discussing this week was published in JAMA Network Open and follows a familiar pattern seen in nutritional epidemiological studies.

Chapter 2: Study Overview and Methodology

Approximately 100,000 healthcare professionals participated in this study, completing a food frequency questionnaire every four years. These questionnaires typically include a wide range of dietary inquiries.

This particular study posed 130 questions regarding various dietary habits, such as the frequency of consuming bananas, bacon, and olive oil. Participants were monitored over a span of more than two decades, and if a participant passed away, the cause of death was classified as dementia-related or not. During this period, around 38,000 deaths occurred, with 4,751 attributed to dementia.

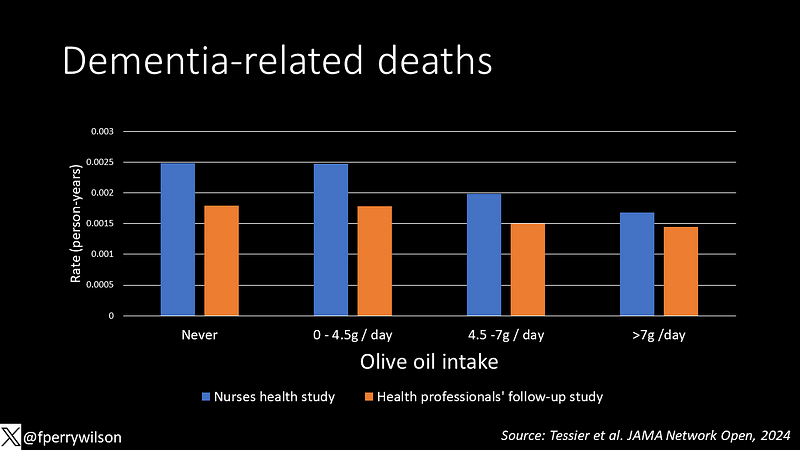

The results revealed that individuals who reported higher olive oil consumption were approximately 50% less likely to die from dementia when comparing those consuming over 7 grams daily to those who reported no intake.

However, we could conclude here if we wished—I'm sure the olive oil industry would appreciate that. But it is essential to delve deeper.

Chapter 3: Limitations of the Study

This study shares the common pitfalls associated with nutritional epidemiology. Firstly, individuals don’t typically consume olive oil in isolation. It is usually paired with other foods. The food frequency questionnaire indicated that those who consumed more olive oil also tended to eat less red meat, more fruits and vegetables, and more whole grains, among other dietary changes. I suspect that those who consume more olive oil likely eat more tomatoes as well, although such granular data isn’t provided.

Additionally, the foods one eats can indicate those they avoid. For instance, olive oil consumers were less likely to use margarine, which, at the time of the study, was often contaminated with trans fats—substances known to adversely affect vascular health. Thus, it’s possible that olive oil is not inherently beneficial; rather, it may simply replace other unhealthy options.

The other significant issue with such studies is that dietary choices are not random. The demographic that consumes olive oil typically differs from those who do not. For instance, olive oil tends to be more expensive; a 25-ounce bottle currently retails for about $11.00.

In contrast, a comparable amount of vegetable oil costs about $4. Isn’t it intriguing that higher-priced foods often correlate with better health outcomes? Perhaps it’s not solely the food itself but also the socioeconomic factors associated with it. While the study does attempt to adjust for these variables, such as using census tract data as a proxy for income, these adjustments may not be entirely accurate.

Chapter 4: Supporting Evidence from Other Research

The authors recognize these limitations and strive to account for them. Their multivariable models adjust for various dietary factors and attempt to incorporate income considerations. Nevertheless, the adjustments may not fully eliminate confounding factors, and the modest effect size observed could still stem from residual confounding.

Now, I mentioned earlier that there’s a compelling reason to consider the validity of this study, but it actually derives from another research project—the PREDIMED randomized trial.

Conducted in Spain and published in 2018, this trial involved around 7,500 participants who were randomized to receive either a liter of olive oil weekly, mixed nuts, or small non-food items. The premise was straightforward: having olive oil readily available would encourage its use. Participants who received olive oil exhibited a 30% reduction in cardiovascular events. Additionally, a secondary analysis indicated a 65% lower incidence of mild cognitive impairment among those assigned olive oil. That’s quite an impressive finding.

In conclusion, while there may indeed be some merit to the claim that olive oil could be beneficial for brain health, I’m not yet convinced enough to include it on my list of enjoyable yet healthy foods. However, it does make me wonder if we could fry French fries in it!

This video titled "Is Olive Oil Brain Healthy? Hope Springs Eternal" discusses the potential benefits of olive oil on brain health and provides a detailed analysis of the associated study.

Another insightful video, "A drizzle a day of olive oil is enough to boost brain health," highlights the positive effects of olive oil consumption on cognitive functions.