Why Is Blue So Uncommon in Nature? Exploring the Rarity of Blue

Written on

Chapter 1: The Fascination of Blue

A few summers ago, I encountered a remarkable creature stuck in our living room window. As I opened the window to assist it, I took a closer look. Up close, this tiny being was truly astounding: its head and thorax shimmered in a brilliant, metallic peacock blue. As it moved, the color seemed to transition from the teal of a tropical sea to the deep blue of a night sky.

Photo by Jairo Alzate on Unsplash Such striking colors are seldom observed in organisms this far north of the equator, so I was surprised to learn that the species I saw, Chrysis ignita, is common in the UK. Yet, I have only encountered it once. What made this particular wasp so captivating to me?

In contrast, its relative, the yellow jacket (Vespula vulgaris), hardly inspires the same awe in our home. While the yellow jacket also boasts a beautiful display with its bright yellow and black stripes, it often becomes a bothersome presence in autumn, seeking out sugar.

Photo by Colin Davis on Unsplash Setting aside the yellow jacket's sugar-seeking habits, one can appreciate its contrasting colors. Yet, do we celebrate the unassuming yellow jacket? Not particularly. This could be because blue has consistently been favored as the most loved color across many cultures, and in the realm of nature, blue is remarkably rare.

True Blue: A Rarity

Consider some blue creatures: the blue peacock, blue macaw, or the infamous blue morpho butterfly found in the tropical regions of Central and South America. All of these are strikingly blue — the kind of vibrant hue that captures your attention immediately. However, nature is playing a trick on us; these creatures aren’t truly blue in a chemical sense. What we perceive as blue is actually an optical illusion.

A Deceptive Illusion

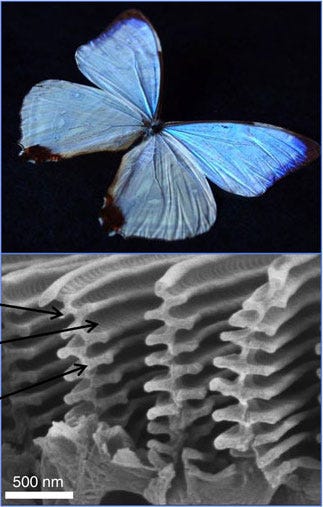

Take the blue morpho butterfly as a prime example.

Upon closer inspection, we find that the wings exhibit an iridescent blue sheen, made up of numerous layers of tiny scales. If we examine it further with a scanning electron microscope, we observe many tree-like structures. These structures serve as an extraordinary example of evolutionary engineering — when light hits the wing, these structures reflect different wavelengths of light uniquely: longer wavelengths (red) interfere destructively, while shorter wavelengths (blue) reflect constructively. This phenomenon allows only blue light to be reflected, giving the wings their blue appearance.

Left: Photo by Michal Mrozek on Unsplash, Right: Photo by Jeremy Zero on Unsplash Many organisms, from brightly colored feathers to beetles, utilize this same physical trick to appear blue. This method of creating blue color is known as structural coloration.

The Scarcity of Blue Pigments

The blue in your favorite jeans results from dyes that absorb all other wavelengths of light except for blue. This reflects blue light, making the jeans appear blue. In nature, however, blue pigments are extremely scarce — fewer than 1% of animals possess a blue pigment. One of the few examples in the animal kingdom is the olivewing butterfly from the Nessaea genus.

By Thomas Bresson, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons In the plant kingdom, blue is also uncommon, with less than 10% of flowers displaying a blue hue. Plants often use pigments like anthocyanins, which change color with pH levels. For instance, red cabbage contains anthocyanins, which can turn blue in alkaline conditions — a classic chemistry experiment involves using red cabbage juice as a pH indicator.

By Indikator-Blaukraut.JPG: Supermartlderivative work: Haltopub, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons So, the next time you find yourself outdoors in late summer and come across a cluster of vivid blue cornflowers, take a moment to appreciate this rarity in nature.

Photo by Irina Iriser on Unsplash

Chapter 2: The Science Behind Blue

In this video, "Why Is Blue So Rare In Nature?", we delve into the reasons behind the scarcity of blue in the natural world, exploring fascinating examples and the science behind this phenomenon.